Social Mapping – Integrating social mapping in teaching and learning

A further aim of our project is to build a set of educational and learning resources which teachers, youth leaders, educators, parents, guardians, and young people themselves can pick up and use as learning tools. We will be mapping these resources to the curriculum, and building them into appropriate packages to share with educators, but in the meantime, here are a number of ways you can include social mapping in learning in primary, secondary or alternative educational settings

Within the Public Map Platform, we define social mapping as the process of mapping places that are used socially and hold social value for children and young people. In our earlier blog, we have discussed the methods and tools we use to engage children and young people in identifying and mapping their social places. The aim is to use the data gathered from this work to build the social mapping layers of the Public Map Platform– i.e. a map of places where children and young people play, socialise, and identify as important to them.

The goal is to better understand the places that local children, young people, and eventually adults, value as social spaces —and to highlight where improvements to these spaces may be needed.

Developing the social mapping layer on the Public Map Platform is, in itself, an experimental process, as it is not without risks. Mapping social places raises ethical challenges and prompt important questions about how we define and share information about place. For example: Do children and young people want to share their social places publicly? Which types of social spaces should —or should not— be visible in the public domain? And how can we ensure that the mapping process represents the whole local community fairly? These are the kinds of questions this project seeks to explore.

Beyond this, a further aim of our project is to build a set of educational and learning resources which teachers, youth leaders, educators, parents, guardians, and young people themselves can pick up and use as learning tools. We will be mapping these resources to the curriculum, and building them into appropriate packages to share with educators, but in the meantime, here are a number of ways you can include social mapping in learning in primary, secondary or alternative educational settings:

- Write and draw about places: Using creative drawing and writing methods, children and young people can express how they feel about places and how they socialise in them. Using some of the methods above – i.e. imaginative mapping, or working on larger paper maps of a neighbourhood or area – mapping places we like, dislike, want to improve, and mapping how we use places, can build a stronger understanding of the geography of a locality.

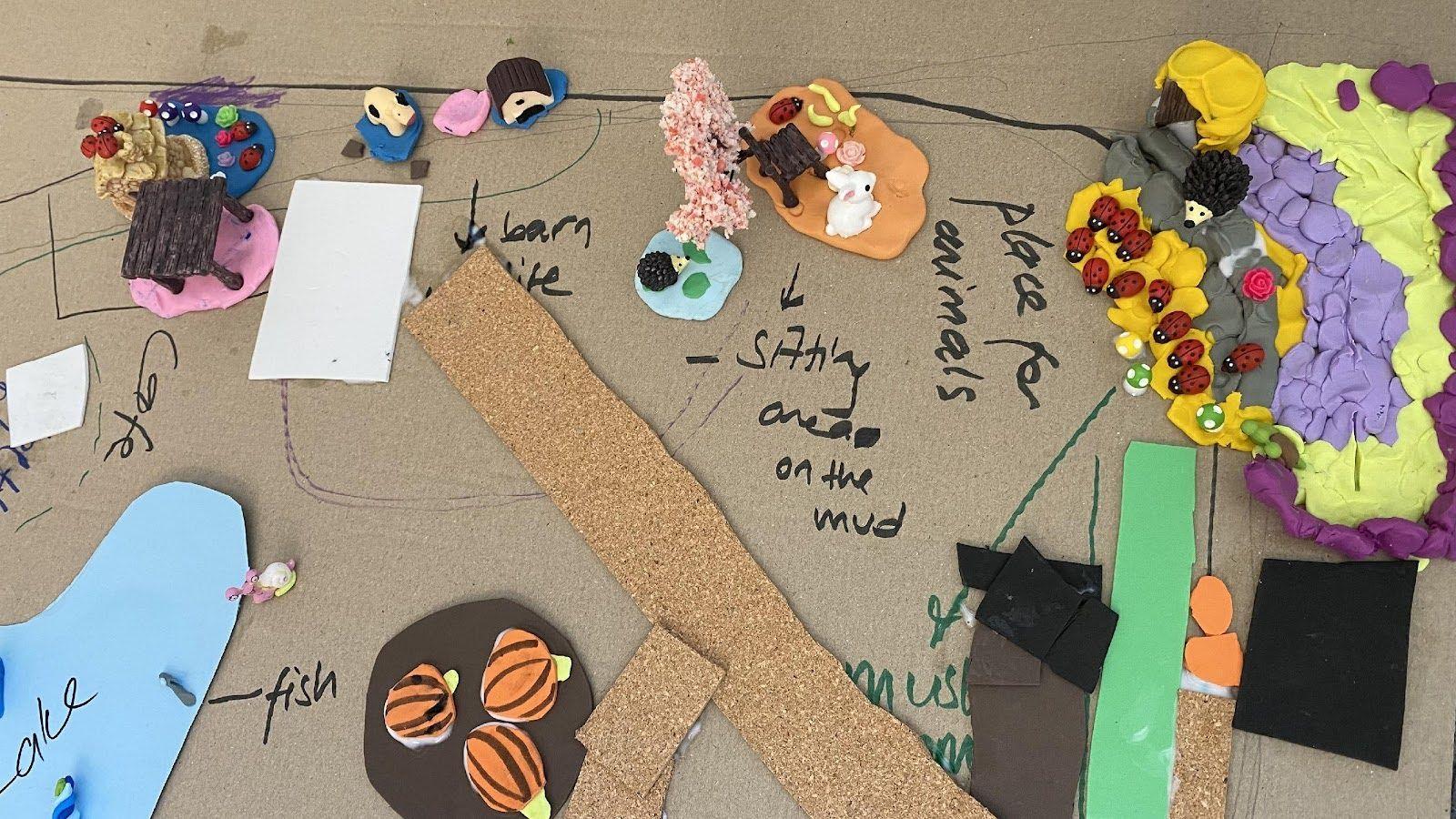

- Be an urban planner or designer for a day: Using the walk-and-talk method described in the earlier blog post, children and young people can – just like urban planners do – assess their neighbourhood for how appropriate it is for their own needs and those of others. In previous research, we have then followed this activity with asking children to re-design public or park spaces or draw overview neighbourhood plans. These can be drawn or made into simple models using basic model-making and craft materials. This activity can enable them to learn basic skills in urban planning and design, and appreciate some of the challenges around neighbourhood development, infrastructure, and how different facilities are used (or not) by different groups. This can be a fun and creative activity!

- Create your own bespoke map: The online tool uMap can be used to create all sorts of bespoke maps. Particularly older young people might be interested in creating their own project based around mapping particular neighbourhood resources, environmental issues and impacts, or other elements of society, by creating their own uMap on the platform. Using the tool to create your own data layers, and in turn mapping these – even using them for fieldwork mapping in-person with mobile devices – can enable young people to generate a map that is meaningful for them and could demonstrate some of their project working skills (for example, for a school-based Geography project).

- Think about what you need now, in 2-3 years, and in 5+ years: Using the pyramid prioritisation exercise described in the earlier blog post, children and young people can identify the areas most in need of improvement. This process can help develop their negotiation skills as they discuss with peers why certain improvements are necessary and why they should happen now. In our previous projects, we also used a sorting card exercise where children created cards with their own ideas for improvement. They then designed symbols to represent these ideas and categorised them into short-, medium-, and long term priorities.

Do you want to engage children and young people in social mapping?

While we are finalising the educational resources based on ‘social mapping’ within the Public Map Platform, you can explore a toolkit we co-produced and used in our earlier projects. The toolkit, Co-creating a Neighbourhood Plan with Children and Young People: A Toolkit for Planners, Designers, Teachers and Youth Workers, includes a bespoke set of activity plans designed to help educators, designers, and planners engage children and young people in mapping their current neighbourhoods and envisioning future improvements.

Please keep an eye on the Public Map Platform website and blog for the latest updates on educational resources for teachers and if you would like to know more about social mapping, please contact us and reference this article.